Phil Ivey and Cheung Yin Sun brought edge sorting to the attention of millions when Ivey admitted he edge sorted at Crockfords Casino in London in 2012. As you surely know, in October, 2014, Ivey lost his lawsuit to recoup his $12M in winnings from Crockfords. Subsequently, Ivey was sued by the Borgota casino for $9M. Ivey was determined to have edge sorted with Sun at the Borgtata, and $9M is the amount Ivey and Sun won during the period they employed this technique. That case is ongoing. On June 2, 2015, Cheung Sun lost her bid to recoup $1.1M confiscated from her by Foxwoods Casino in 2011, after it was determined she used edge sorting.

Edge sorting isn't doing very well in the courts these days. Maybe a better way to say it is that Phil Ivey and Cheung Sun aren't doing very well in the courts. I know of many instances of edge sorting that were not prosecuted in civil court. The APs got to keep their winnings without a legal battle (one such story is presented below). But when the amounts get into the "millions" range, people get pretty serious about these things.

For more about Phil Ivey and edge sorting, I recommend these posts:

- Phil Ivey -v- Crockfords

- Podcast on Bluff.com about Phil Ivey

- Phil Ivey and Yellow Journalism

- Beating the House: From Affleck to Ivey

The following story presents my first real-life experience with edge sorting as a consultant ... turns out it was Cheung Sun's team.

About three years ago I was playing double-deck blackjack at a large off-strip casino in Las Vegas. OK, I admit, I was counting cards. But, honestly, I was just passing time waiting for someone I was going to meet for dinner. And besides, it’s hard not to count when I play. With a minimum bet of $5 and a maximum bet of $40, I was not a threatening presence. My hourly wage from this activity was about $8 - $10 on a good day. But at this point in my career, it was no surprise, indeed it was embarrassing, when I quickly got a tap on the shoulder.

I turned around and a well dressed man introduced himself as the table games shift manager. He said “Dr. Jacobson, we know who you are. What are you doing?” It was an awkward question and he was clearly uncomfortable asking it. And I was embarrassed as well. As I got up from the table, we engaged in some casual conversation that blew off some steam for both of us. Talking about security matters in a general way, we gradually became focused on bigger problems. I asked: “If there’s anything at all going on here that you want me to look at, any issue of security you can’t figure out, let me know and I’ll give you my opinion.”

What happened next was even more surprising. The shift manager explained that for the previous several months the casino had been hit hard by a card marking team. He said, “They seem to know what the cards are when they play.” But as he explained, the casino had carefully examined the decks again and again and could find no indication of the marks the team was leaving. He was sure they were marking, but there were no marks. How could that be?

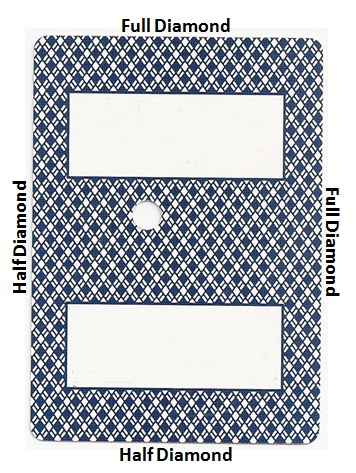

I asked him to show me a deck of cards. He motioned to me to accompany him to a table in a closed pit and pulled out a fresh deck. The card pictured below is the card used by another Las Vegas casino, but it is similar to the one I saw. The striking feature of this card is that it is asymmetric. Two adjacent edges of the cards clearly have a blue half-diamond shape, while the other two edges clearly have a blue full-diamond shape. And every card in every deck had this feature.

The fact that the design is asymmetric allows the cards to be rotated by an edge-sorting team. The way this works is that a table is occupied by players who work together to rotate the cards to help read their values before they’re dealt. Certain key cards are rotated to have the full diamonds across the top and right edges, while other cards are rotated to have the full diamonds on the bottom and left edges. For example, in blackjack, Aces and ten-valued cards may be rotated one way, while all other cards are rotated the other way, allowing the players the ability to read the dealer’s next card. Of course, the cards will get mixed up, but the team continues to sort them every hand, and after a few shuffles, most of the cards will be sorted. The fact that the casino deals, collects and shuffles the cards according to strict procedures is the Achilles' heel.

I told the shift manager, “An easy fix for this is to have a turn in your shuffle. You do have a turn, don’t you?” His face showed a shade of white that would make Mary’s little lamb jealous and confessed that their shuffled did not include a turn. They had spent months investigating the way the team was marking their cards, while all along the cards that were being used were pre-marked. The team was using this casino’s own procedures and equipment against them. After a few minutes of taking it all in, my new best friend told me that he would be in touch and gave me his card. Needless to say, I never heard from him again.

I am not saying that casinos that use this type of playing card are making any type of mistake in their choice of product. Cards that can be edge-sorted are in wide use. Surveying my own collection of about 50 decks from various casinos, over two-thirds of them can be edge-sorted. The solution is to understand the particular security weakness of this type of equipment and to put in a trivial procedural fix. Every shuffle, whether it’s from a single deck, double-deck, or shoe, should include a turn. Likewise, any game that uses an automatic shuffler should include a manual turn between rounds. The equipment being used wasn’t the problem – it was the procedure for using the equipment that was flawed.

I was recently visiting a casino that used a card that had the edge sorting problem. I observed their blackjack shuffle, and sure enough, it had a turn. I then asked a pit supervisor why the shuffle had the turn. The answer was dead on: “so the cards can’t be identified by some pattern on their backs.” I then went to the novelty game pit, where automatic shufflers were being used, and observed that no turns were in place. Clearly someone in management understood the need for a turn and that message was transmitted into the policies and procedures in the main pit. But, like may casinos, they didn’t take the protection of their novelty games seriously. Bad idea.

The lesson here is that nothing can be taken for granted in protecting games. Often the problems are little and can be quickly fixed. But unless you know the problem and know the fix, you may spend months wondering what they’re doing and how they’re doing it. Persistence is not always the answer to solving a problem.